How Failing to Lead by Example is Falling Short on Impact

Why public interest technology must rethink the talent pipeline

By Jenn Noinaj, Beeck Center Fellow

Right now, in response to the systemic vulnerabilities uncovered by the COVID-19 pandemic, the movement to apply technology for the greater good is gaining more momentum both in terms of investment and interest from talent in tech and government alike. But it raises an important question: are the right people showing up to build this movement?

Public interest technology, as this field is increasingly referred to, leverages data, design and technology to create better systems that work for all by centering equity, inclusion, impact, and access. That commitment to equity, and the belief that solutions must be inclusive from conception through completion, means ensuring that the field itself is representative of the diverse communities that public systems serve. Unfortunately, as it stands, this new discipline looks too much like the existing world of “Big Tech” to make a lasting impact on society in a substantially different way.

The Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation at Georgetown University recently surveyed nearly 200 self-identifying public interest technologists from across the field to understand whether the current demographics align with our field’s stated goals. Our respondents were mostly early adopters — individuals who have been charting and shaping the field over the past 10 years.

We learned a lot from this survey, including that the majority of respondents had experience working in government at the federal level, and that the most common role was designing or developing tools as opposed to research or measurement. We were disappointed to discover that the workforce is falling short of its promise to reflect the public in order to better serve it; 5.2 percent of our respondents were Black and 3.3 percent were Hispanic or Latino, compared with 12.4 percent and 18.7 of the U.S. population, respectively, based on the 2020 Census. When we consider how the design and implementation of government services and policies (from lending to voting access and safety net benefits) have often excluded communities of color intentionally or otherwise, one thing is clear: the public interest tech pipeline needs to redouble its efforts to bring in diverse and inclusive talent from the bottom up. Said simply, we need to walk the talk if we want to make public interest tech work for all of “the public.”

Despite touting mission-driven work that strives to deliver services equitably, the overall demographics of public interest tech workers aren’t any better than the overwhelmingly white, Asian, and male workforces reported by Apple, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft.

When systemic inequities persist in our public interest tech pipeline and exclude diverse, dynamic and qualified people, any positive impact the field can have is hampered from the start.

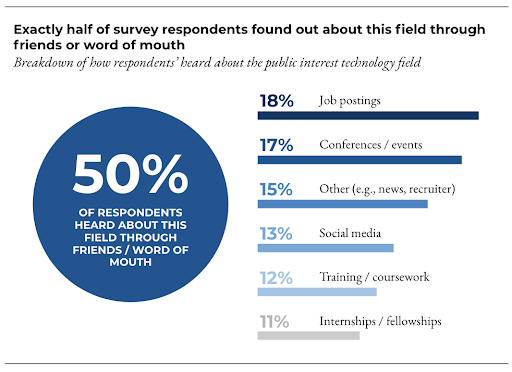

Our survey also found that most people in public interest technology have at least three years of work experience before entering the workforce, making the entry-level career pipeline weak. As part of a university training the next wave of public interest technologists, this is a challenge the Beeck Center knows well, and we have our work cut out to address it. Furthermore, the field continues to be driven by insular networking: 50 percent of respondents in our survey indicated they heard of opportunities primarily through word-of-mouth. The result is a workforce that continues to be concentrated within the D.C.-beltway and predominantly upper-middle class, with an average income of $119,242.

The problem is further amplified by recycling talent through organizations and creating an echo chamber — where instead, there should be a renewal of innovative ideas and skills from new entrants.

Even after recruitment into the field, workers who hold marginalized identities often feel disenfranchised by their organization’s culture. Seventy-three percent of those who reported that they feel like they do not belong at their organization identified as BIPOC, female, genderqueer, transgender, and/or disabled. This is a problem.

We must be unafraid to use the same lens we espouse to solve the challenges in our own recruitment and development. Non-governmental groups like AnitaB, Aspen Tech Policy Hub, Coding it Forward and Tech Talent Project are leading the way, building new pathways into the public workforce. At the Beeck Center, we recognize how important having an inclusive community will be to meeting this challenge, so we helped launch the discipline’s first professional association, Technologists for the Public Good, to give practitioners a place to turn for mentorship, advice, and career development.

The stakes are high. All tech has a public interest — technology is all around us, and it interacts with everyone in one way or another. To build technology that truly serves the public interest, we must pay attention to who is designing and building the technology and related policies first. We can’t just make change; we need to model it. By building a culture that centers the voices of those most often excluded or oppressed by our current systems, we can ensure that our technology and socio-technical systems better serve the public at large.

We know we’re talking about uncharted territory, but we’re up for the challenge. The issues we find are not unique to our field, but some of the solutions may be. If the pandemic has taught us anything, it is that we can write new rules. We can make things work better, but we can’t wait until the next global crisis.

Jenn Noinaj is a fellow at the Beeck Center who has led the Public Interest Technology Workforce project, focused on resources to support the growing field of public interest tech. Follow her at @actuallyj3nn.